For Reference Links Click Here: Reference Links for Selling Smoke Bluffs Article

For FMCBC Response Letter Click Here: FMCBC Response - Smoke Bluff Lands 15 Dec 2020

Executive Summary

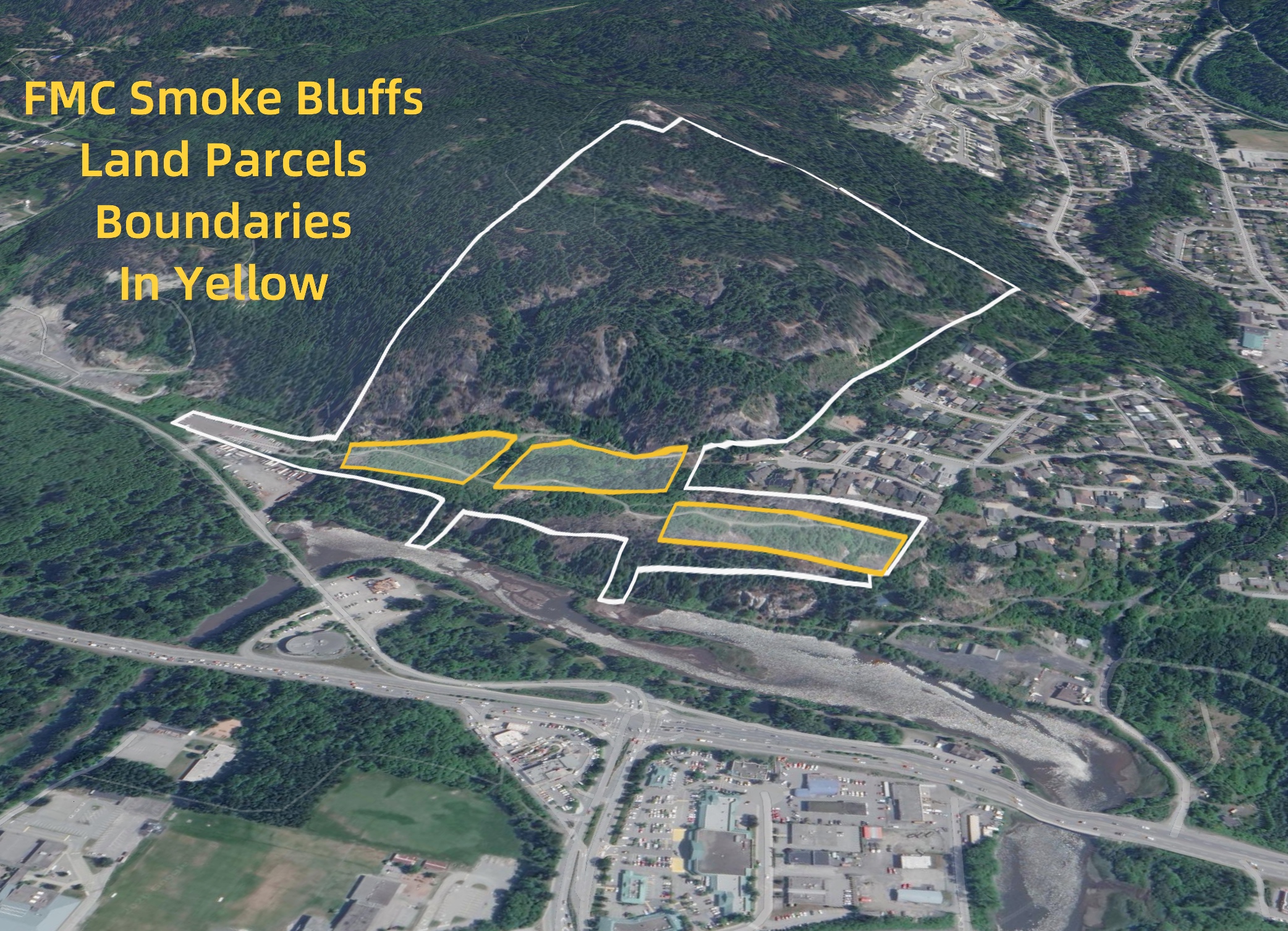

The Federation of Mountain Clubs of British Columbia (“FMCBC”) may be considering selling the three land parcels it owns in the Smoke Bluffs Park (the “Park”) to the District of Squamish (the “District”). It has owned those parcels since 1986/87, and their sale would be irreversible. The benefits would be minor and short-term; the loss of access leverage for climbers to the most popular climbing area in Canada would be permanent. Legal precedents elsewhere in BC suggest that restrictive covenants on lands transferred to municipalities are not effective, and at the least they require vigilance and resources to enforce. The District has attempted to reduce climbers’ governance role for the Park twice during the last five years. Comparison to practices elsewhere suggests that the best option is to hold such lands in perpetuity, to ensure their continued protection. If FMCBC has a real need to remove the parcels from its balance sheet, it should consider other options, such as a transfer to another climbers’ organization that is also a registered charity.

1. Introduction

This document discusses a hypothetical (but, allegedly, likely if not imminent) sale by the FMCBC to the District of its three land parcels within the Park in Squamish, which it has held on behalf of the climbing community and public for over 30 years. The lands are not within the Park, but are central to its functioning, and managed as though they are in the Park. This document reviews the history of the parcels, the positive and negative aspects of a sale to the District, and the District’s recent changes in the Park’s governance, and suggests some alternatives.

2. Scope, methodology, context, etc

Like the proverbial iceberg, much rumour and conjecture lies below what is visible and acknowledged in this situation; none of which can be verified at the current time. To avoid the risk of slandering anyone, this document is assembled as strictly as possible from public domain information. It only includes information gained verbally where that has been confirmed by at least one other third-party. (Note: Since the creation of this document, much as been now verified).

3. History of the parcels and the Park

Although details are not known, the Bluffs were probably the scene for some of the first (intentional) rock climbing at Squamish, in the mid 1950s. They were long used by residents for moderate hiking, and in the mid 1970s rock climbing there began to grow very quickly. In 1987, a number of contiguous land parcelswithin what is now the Smoke Bluffs Park were put up for sale by a private land-owner. The parcels formed the bases of Burger and Fries, Smoke Bluff Wall, Crag X, the left side of Neat and Cool and other cliffs. They also formed a potential legal access route for climbers between the Loggers Lane and Hospital Hill road access points. Though only about 3.5 hectares in total, the parcels were the only flat benchlands in the immediate area and therefore were attractive to property developers. (In contrast, the steeper cliff areas above, which the District had been gifted by the province some time previously, were undevelopable.) The parcels were likely to attract other offers, development of a road through them had begun, and so climbers had to act fast to secure the lands.

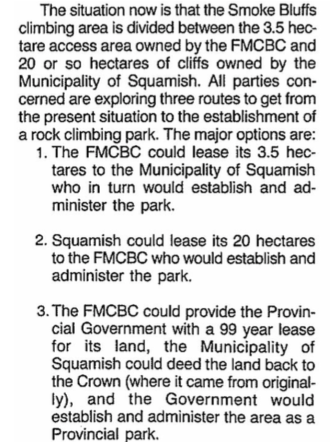

The story of the FMCBC’s purchase of the parcels is well documented in several places, like this article, originally written for Canadian Alpine Journal and reproduced in Gripped magazine, and in the history sections of various Squamish climbing guidebooks. Extensive context from FMCBC’s perspective can be found in the FMCBC’s Cloudburst magazinein 1987. For example, the summer 1987 magazinecontains a detailed account of the FMCBC board’s intentions for the parcels. These paragraphs below are especially relevant to the current situation:

It was never envisaged that the land be sold, only leased.

At the time, FMCBC was the principal access advocacy group in BC for climbers, mountaineers and hikers and it was typical that many people had a common interest in all these activities. Amongst other things, the purchase of the land and related matters led to the formation of a small grass-roots climbing group, the Squamish Rock Climbers Association (“SRA”) - few climbers then lived in Squamish. Over the next few decades, in parallel with a tendency to specialization in these activities (not all rock climbers are mountaineers, etc) came some splintering of the access effort, with the appearance of Climbers Access Society of BC (“CASBC”) in 1995, and the SAS in 2006. All these groups, together with the FMCBC, lobbied for creation of a Smoke Bluffs Climbing Park, in line with the objectives cited above. BC Parks rejected the idea of it becoming a provincial park, and while Squamish remained primarily an industrial town, the District had little interest in the topic.

The FMCBC undertook several trail-building projects in the Bluffs through the late 1980s and early 1990s, prepared a professional park proposal study, and did what it could to interest civil servants and politicians in the idea.

That situation changed in the mid-2000s. The sawmill by the Blind Channel and the pulp mill at Woodfibre had both closed by 2006 and Squamish contemplated a post-industrial future. A new mayor, Ian Sutherland, was elected in 2002 as part of a “Squamish New Directions” slate. His vision for the town included a greater role for outdoor recreation. Between 2004 and 2007, his council worked with CASBC (including its Squamish representatives), the FMCBC and the other groups toformalise a Smoke Bluffs Park, comprising the FMCBC parcels and the District lands above. A key component within the Park concept was a governance structure that protected rock climbing as the principal use of the Park and gave climbers a guaranteed majority on a Park management committee (currently called the Smoke Bluffs Park Select Committee, “SBPSC”). The next two councils, under Mayors Greg Gardner and Rob Kirkham, respected that agreement and broadly allowed climbers and other volunteers to manage the Park and build trails and other infrastructure within the Park as they saw fit, indeed with considerable financial and other support.

From 2014, under a new mayor, Patricia Heintzman, and new leadership within the District’s staff, the status quo of the Park came under some new scrutiny. A freshmanagement planwas drafted between 2015 and 2017. Subsequently the Bluffs bylaw came before council for change on two separate occasions in 2017 and 2019. These events and their significance are described in section 6, below.

Unconnected to any Smoke Bluffs issues, the FMCBC’s largest component club, the BC Mountaineering Club (“BCMC”) resigned from the federationin 2018. The resignation letter stated that:

“Due to increased population pressures in the province, an increasingly large number of access issues are not being resolved, particularly in the lower mainland. We require a stronger, harder hitting advocacy program to resolve these issues than the FMCBC is prepared to provide.”

One effect of this change was to endanger FMCBC’s financial situation, as the federation is primarily funded by a levy on its component clubs, based on those clubs’ member count. For example, in the2020 reportof one of the FMCBC’s remaining large mountaineering clubs, ACC Vancouver, director Jay MacArthur writes:

“There are some administrative issues in the FMCBC. Since the current Executive Director (Barry Janyk) was hired three years ago the FMCBC has been posting financial losses. Losing the BCMC hasn’t helped that situation. Currently each club pays only $8 per year per member towards the FMCBC. So for the ACC-Vancouver section that is currently about 800 x 8 = $6400. Other clubs also pay another $12 per year for insurance but we get insurance from ACC National. Ideally if the FMCBC wants to keep a full-time executive director, the member dues will have to increase to about $15/member or some other fundraising efforts will have to be successful.”

At the time of writing, the FMCBC reportedly has a sub-committee reviewing the Smoke Bluffs land holdings. There has been no other public disclosure.

4. Positive aspects of the FMCBC parcels being sold to the District

a. Release funds for other access use

The District recently paid $650,000 for the Drenka lands,close to the FMCBC parcels. However these were privately-owned, zoned for industrial use, not readily developable, and not part of the existing Park. The FMCBC’s 2019 annual reportitemizes the Smoke Bluffs land holdings as having a combined book value of $69,184 and also notes that the assessed value is $156,600; a low number presumably because the lands are already within the Park, although not protected in any legally binding manner. (In an open market, without any protections, the FMCBC lands may now be worth millions.) It may be realistic to imagine the District paying an amount somewhere in the book value - assessed value range. That would be a functionally-useful amount to help seed future land purchases where access is threatened, if held solely for that purpose, but clearly not large enough to be transformative.

The executive director position at FMCBC is the only salaried position in access advocacy for climbing and mountaineering in BC. For comparison, The Mountaineers in Washington state (admittedly an organization whose objectives go beyond access) lists remuneration around US$3 million in its 2019 990 IRS filingand has a lengthy staff liston its website. The BMC in the UK, advocating on behalf of climbers and mountaineers in England and Wales has more than thirty employees.There is no doubt that a place of BC’s size, complexity and global significance in mountain recreation should be supporting full-time salaried access people. However, operating expenses for such organizations, such as remuneration, would normally be funded from operating income, rather than from capital. It would be very unusual to sell key long-term assets so as to pay short-term expenses.

It has also been mentioned that FMCBC has had grant applications rejected because its ownership of this land makes it appear “flush”. If true, that is a bona fide concern, but selling out to the District is not the only possible solution.

b. Provide closure and recognition for some access volunteers

The event of the District owning all the lands within the Park boundary would likely be followed by an official dedication ceremony for the Park. Several people have been volunteering time to the Smoke Bluff Park since its inception without an end-point in sight; a dedication event would provide that closure and perhaps some deserved attention to their work. It might also give an opportunity for a short-term reset in the relationship between the District and climbers. Longer-term, however, intangible benefits of this type will likely fade in people’s memories quickly.

c. An opportunity to renegotiate governance for the Park

A land transfer to the District could include restrictive covenants on future land use. Furthermore, as climbers’ influence within the SBPSC has been diminished since the committee was established in 2007, the FMCBC could also insist that a new Park bylaw precede a sale. That bylaw could simplify the committee structure, make climbers’ majority on the SBPSC permanent and attempt to make the existence of the committee independent of council interference. However, a recent BC Supreme Courtrulingon a similar case indicates that it is not possible for these type of covenants to constrain municipalities in the long term.

d. End the FMCBC’s property tax risk

The District currently waives the FMCBC’s property taxes as part of its Permissive Tax Exemptions. The exemption is at the District’s discretion and could be cancelled. However, the amount is trivial in context: $869 in 2019 (see page ten in the District’s annual report).

5. Negative aspects of the FMCBC parcels being sold to the District

a. Betrayal of past efforts

The original purchase of the Bluffs parcels was a prescient and herculean effort. Jim Rutter, then Executive Director of the FMCBC, provided much leadership then and later. John Randall, its then president, financed the initial transaction, taking a risk on the climbing community being able to pay him back. MEC, a much smaller organization in 1987, then repaid Randall, and held a mortgage as security for the loan – although it also forgave much of the loan. It was repaid in less than a decade, Numerous volunteers, particularly from the BC Mountaineering Club, the Alpine Club of Canada – Vancouver Section, the Varsity Outdoors Club, and the SRA, put amazing effort into fundraising and educating. Some of their lungs are still recovering from the hideous casino nights, which were the main source of funds to repay MEC’s mortgage.

As the extract from Cloudburst magazine above details, the decision-makers at that time did not envisage the land being sold, only, in the right deal, leased. Selling the land parcels in contradiction to the historic donors’ intentions could discourage donations to future access land deals.

b. Irreversible loss of leverage

A sale of the parcels would be irreversible; an obvious and short statement but really the heart of this issue. Ownership of the land gives climbers leverage over the administration of the Park, and ensures that the entire area remains protected, with climbing is the principal activity in the Bluffs.

At the current time it may require some imagination to consider possible risks to the Park’s status, but they certainly exist. Some examples:

-

- The District experiencing a liability scare regarding climbing, especially fixed equipment like anchors.

-

- The District coming under pressure to repurpose parts of the Park for residential use. For example, providing below-market-rate rental housing is already an overt objective of the current council but the District has a very limited number of land holdings on which to build.

-

- A municipal bankruptcy scenario, in which the District land assets might need to be sold to restore solvency. Again this may seem unlikely to some but the District has skated on thin ice quite recently, for example, through its handling of the ex-industrial Oceanfront lands that it received for a dollar in 2004 then proceeded over a decade to turn into a $12 million debt.

The FMCBC Lands are a source of leverage for climbers in these scenarios not only for the moral high ground they represent (“we climbers saved this land from development for the benefit of all”) but also for less-abstract transactional reasons. Currently the main ”commuter trail” through the lower part of the Park, used by a diverse number of Squamish residents, especially bike commuters and dog-walking hikers, lies almost wholly on FMCBC land - though few people realize this. The FMCBC could threaten to close those trails if the District were threatening changes unacceptable to climbers in the use or governance of the Park as a whole. Clearly trail closures would be a “nuclear option”, only to be considered if negotiation failed. However developers shamelessly employ these kinds of tactics; in fact there is a current example elsewhere in Squamishof the District being pressured in this way.

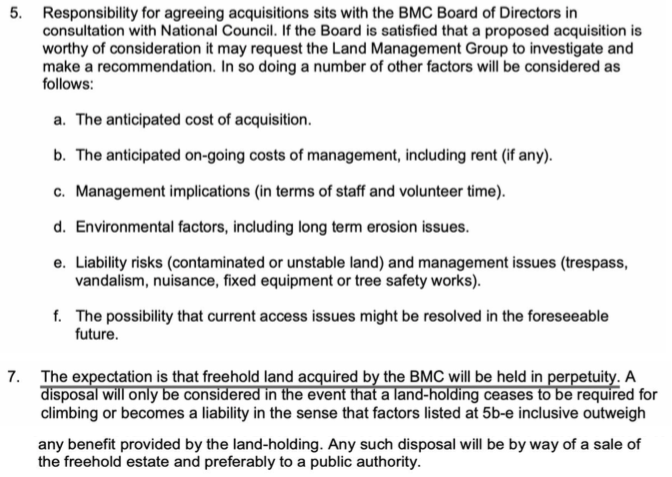

c. Inconsistent with best practice

The UK’s British Mountaineering Council (“BMC”) is one of the longest established climbing access groups globally, formed in the 1940s. It has been using land purchases as part of access solutions since the 1970s. The BMC has established policies for access land that it does not publish (From the Access & Conservation Officer, who, coincidentally, attended the 2018 Arc’teryx Mountain Festival in Squamish:“It’s not a document we particularly make an effort to publicise as it’s pretty niche and we don’t necessarily want landowners to know the detail of our approach to land acquisition so as not to generate a market for selling crags to guarantee access.”)but will share on request. Items #5 and 7 of their policy document state their normal policy “land ... will be held in perpetuity” and very restrictive criteria for disposal:

BC is not the UK, but these policies are generic and applicable anywhere. Using their template to evaluate the Smoke Bluffs, none of the “5b-e factors” are material. On that basis, there should be no disposal of the land.

6. Recent changes in SBPSC governance

A common comment in relation to this topic is that “Squamish has changed”, that somehow the outdoor-recreation-scornful District of the 1980s/1990s was an anomaly, and the pro-climbing District of the early 2000s the new normal. First, of course, these types of generalisation are just that, and not really practical guides to interacting with government; skepticism toward government is surely always wise? Second, the recent evidence is not at all positive.

As mentioned earlier, the management committee bylaw came before council for change on two separate occasions in 2017 and 2019.

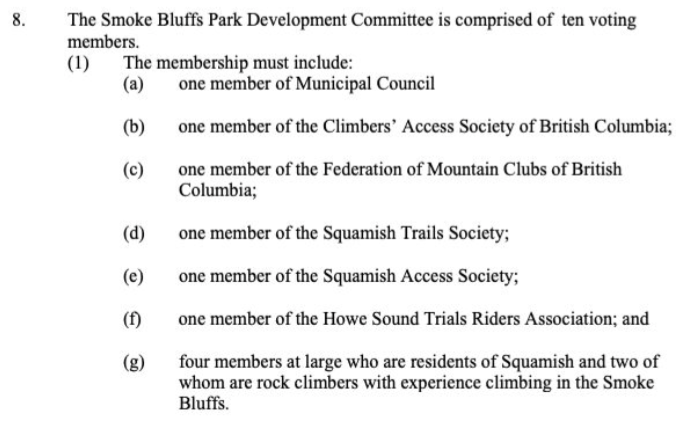

The 2017 change came out of the blue in early January. Climbers only had a handful of days to organize a response. The key item within the bylaw changeswas a restriction on who could occupy the chair and vice-chair positions on the committee. Had it been passed, only members-at-large on the committee, being four appointees at the discretion of District council, could occupy the chair or vice-chair positions. The bylaw-mandated composition of the committee in 2017 was:

Up until that point most chairs of the committee had been provided from the society-appointed members of the committee, in particular SAS, the most “local” of the climber access groups. The change would have severely limited climbers’ ability to shape policy for the Park. Fortunately, SAS and others lobbied the council successfully such that two council members spoke out against the change and that item was not adopted.

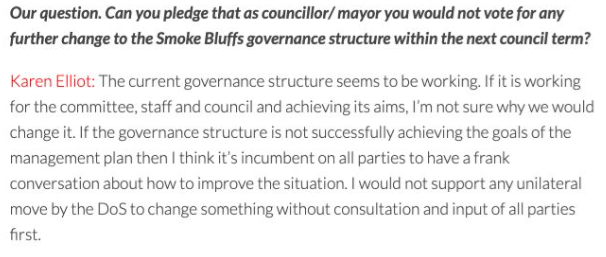

During the 2018 municipal election, there was sufficient concern about council attitudes toward Smoke Bluffs governance that all the councillor candidates were asked by SAS about their position on the topic (along with some other topics). Squamish Climbing Magazine recorded the responses from the successful candidates here. For example, the successful mayoral candidate responded as follows:

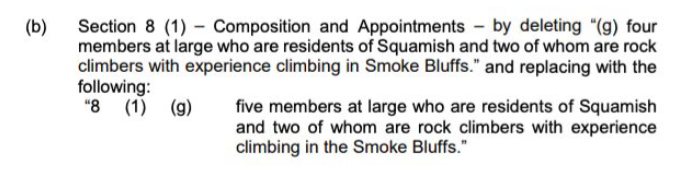

undertaking just a few months before, there was no “consultation and input of all parties”. Wording as follows (to make sense of this, cross-reference to the bylaw item 8 wording on the previous page):

In February 2019, it was discovered that in the course of routine member-at-large appointments to the SBPSC, council had rejected Wes Staven, a local climber who had done extensive volunteer work in the Bluffs Park including an important survey of the Park boundary in 2016. Instead they had appointed an individual with no volunteer history and unknown to any of the existing committee. SAS and others lobbied the council to reverse this decision. Council’s response was to change the Park establishment bylawto add another member-at-large position. Contrary to the new mayor’s

The effect was that climbers lost their previous institutionalized majority on the committee.Three society appointments (CASBC, FMCBC, SAS) and two must-be-climbers members-at-large are now matched by two non-climber society appointments (STS, HSTRA) and three need-not-be-climbers members-at-large. So far the change has not had dramatic consequences for Park policy, but people close to the situation are concerned.

Though climbers who live in Squamish are now numerous (the local gym has over a thousand season pass holders, almost all of whom are residents) they are never likely to form a significant voting bloc. The town’s population is already over 20,000, and growing steadily. Council members are unlikely to prioritize attention to climbers’ issues over more mainstream causes.

7. Some conclusions and suggestions

Unless the payment being offered by the District were spectacular, creating an opportunity to fund a major access purchase elsewhere, it does not seem that the minor benefits of a purchase outweigh the permanent loss of climbers’ leverage. Even if a sale could be accompanied by strict covenants and a renegotiation of the Park’s governance, it is hard to be confident that those would be honoured in the long term. If the concern were a minor climbing area with a handful of cliffs it might be forgivable to be apathetic. The Bluffs are probably the most popular rock climbing location in Canada.

On the other hand, it is understandable that a group like the FMCBC that has changed focus and structure substantially over several decades, and has financial constraints, might not want to be the Bluffs’ custodian in perpetuity. Some suggestions:

-

If the FMCBC concludes it needs the funds from sale of the parcels,it should state its terms and allow the climbing community the first opportunity to re-finance the asset and find a more stable home. The land would need to be owned, or co-owned, by another organization that is also a registered charity, with the possibilities the Alpine Club of Canada, British Columbia Mountain Foundation, and CASBC. It may be that a “multiple-owner” scenario would provide the most stable long-term protection.

-

If the FMCBC really feels that it is somehow obligated to strike a deal with the District, consider a lease with break clauses rather than a sale. A lease would give FMCBC a new predictable income source while break clauses would maintain some leverage.

-

If the FMCBC decides to retain the parcels, it should remind Squamish of its ownership, and the historic significance of the original purchase, more overtly. For example: a plaque in a prominent place, like the base of Burger and Fries; signage at the points where the main trails enter and leave the parcels; freshly-designed posters in the Parks’ information kiosk; a celebration at the 40th anniversary of the purchase (2027).

-

There will always be a concern that should the FMCBC become insolvent – or be forced into insolvency – its land at the Bluffs will be endangered.

-